Life on the Screen

As a cross-media artist, I am constantly interested in how technical systems impose themselves on the human condition. My project, Life on the Screen, emerged from a desire to interrogate the psychological and social consequences of digital dependency, especially with smartphones and algorithmically designed interfaces. This short narrative film draws on discursive design, speculative narrative, and cinematic storytelling to critically reflect on our increasingly blurred boundaries between online and offline life.

The conceptual foundation of the film draws heavily from the psychological literature on media addiction and the behavioural design of digital platforms (Suler, 2016). I was particularly influenced by Black Mirror’s aesthetic and structural choices, especially the episode “Fifteen Million Merits,” where the protagonist is trapped within a gamified, screen-dominated society. Like the characters in Brooker’s narrative world, my protagonist exists in a digital loop—a void of repetitive interaction, seduced and depleted by endless scrolling, push notifications, and validation loops.

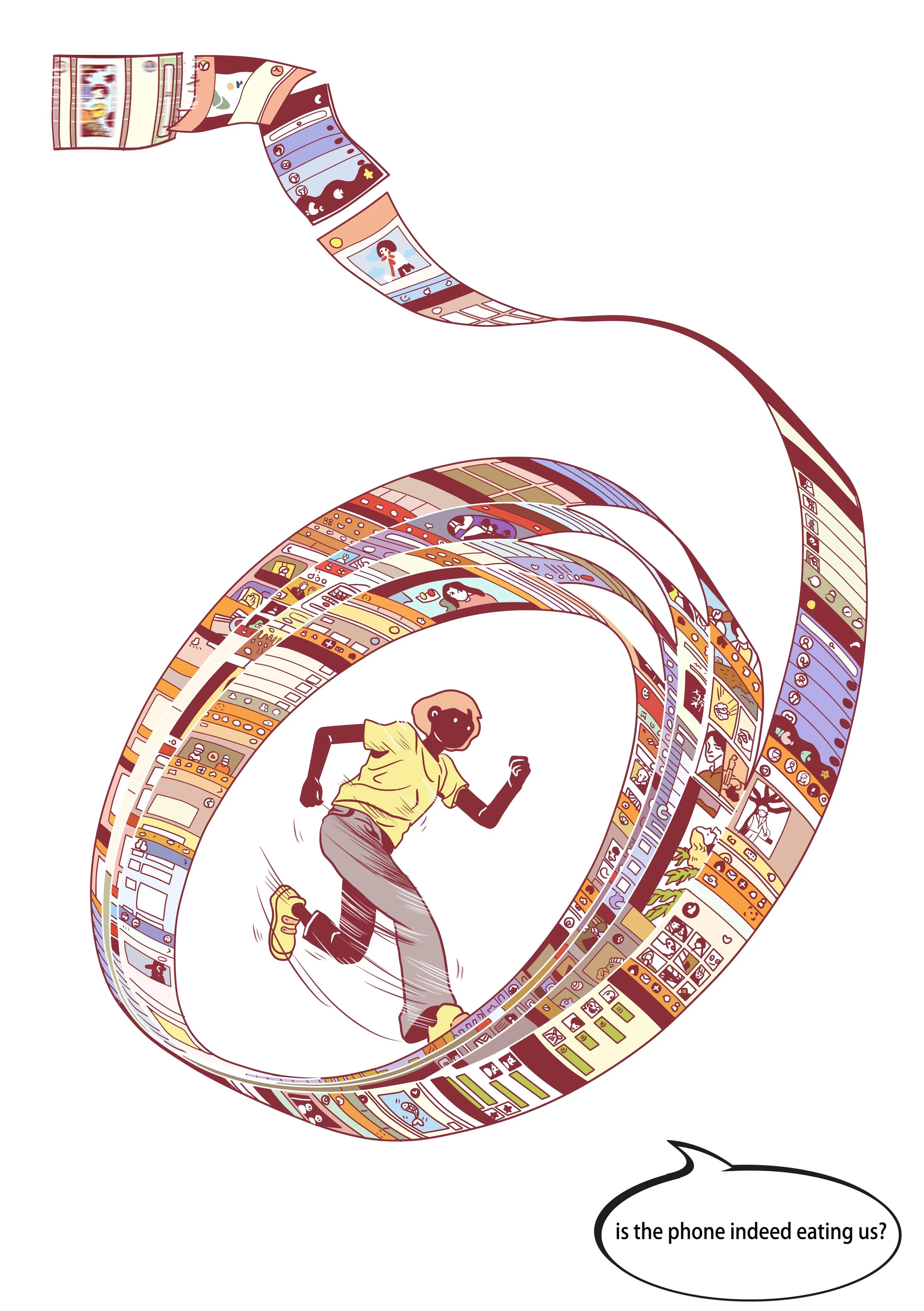

The primary aim of this project was twofold: first, to make visible the hidden architecture of persuasive interface design, including infinite scroll, variable reward mechanisms, and behavioural nudging; and second, to use the language of film—mise-en-scène, performance, cinematography, and editing—as a critical mirror through which viewers might reflect on their own entanglement with devices.

Throughout the production process, I was deliberate in adopting visual metaphors to explore the embodiment of technological dependence. My protagonist’s movements are constrained, automated, or numb, echoing the ways digital systems reconfigure bodily autonomy. The presence of the phone in the film is not merely a prop but an extension of the character’s limb, an appendage whose removal would feel akin to amputation.

Visually, the film is designed with a muted colour palette dominated by cold blues and monochrome screens, creating a claustrophobic atmosphere that simulates the flattening effect of constant digital mediation. I deliberately kept the framing tight, using close-ups and slow pans to reflect the absence of spatial or mental distance. The editing pace is slow and repetitive, looping actions and screen interactions to evoke the psychological tedium of perpetual digital consumption.

The use of voiceover in the final scene serves as a rupture, an invitation to reflect. The voice, distant and neutral, poses a series of introspective questions: “Do you feel your phone even when it’s not there? Do you scroll without knowing why?” These questions are not didactic, but open-ended provocations intended to re-sensitise viewers to the affective and embodied costs of interface dependency.

The theoretical dimension of this work is informed by contemporary discussions around cyberpsychology, interface addiction, and the manipulation of user behaviour through persuasive design. I drew on the research of Silver (2018) and Ahuvia (2013) regarding infinite scroll and attention traps, and related this to my own observations about how platform logics intrude into everyday life. The use of seamless design patterns, while intended to improve usability, often creates a frictionless environment that bypasses user agency. My film aims to reintroduce friction, not as an inconvenience, but as an ethical pause.

Moreover, this project is framed by a broader concern with digital ethics and human-centred technology. While many mainstream discourses celebrate digital innovation, I felt it was important to address the darker undercurrents of compulsive technology use, especially to younger generations. As noted in recent public health studies, overuse of screens has been linked to sleep disruption, anxiety, and cognitive fragmentation. Rather than communicate these effects through data, I chose to express them through mood, pace, and affect.

While the film presents a dystopian tone, it also gestures toward reclamation. In the final moments, my protagonist sets the phone down and looks away, a small but potent act of refusal. It is this gesture that underscores the ethical core of the project: that agency is not lost, but dormant; that attention, once reclaimed, can become a site of resistance.

It visualises the cost of digital dependency not through abstract critique but through lived experience, rendered in cinematic form.

In summary, Life on the Screen is both a narrative artefact and a reflective practice. It visualises the cost of digital dependency not through abstract critique but through lived experience, rendered in cinematic form. I hope that the film invites viewers not simply to reject technology, but to notice its textures, its rhythms, and its power to pause and ask: what is this device doing to me, and why?